|

A Scenario for a New Internet Governance

Carlos Afonso

This chapter is an exercise which seeks to derive a more decentralized organization from the only currently working structure specifically created for Internet governance – what I call here the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) System, which involves ICANN and its supporting organizations, as well as the Number Resource Organization (NRO) and the Regional Internet Registries (RIRs). The chapter envisions governments moving from an advisory to an oversight role in a multistakeholder coordination and oversight body. As to root server management, the proposal calls for joint management of a single root system by a new ICANN and a new Country Code Names Supporting Organization (ccNSO).

Principles and Requirements

This proposal is based on the following definitions and principles:

-

The Internet currently is the global set of computer networks interconnected through IP-based data transfer and addressing protocols, a standardized packet addressing and routing scheme with globally unique addresses based on a centralized set of root servers and zone files, as well as other common information exchange protocols.

Internet governance is the set of Internet coordination and management activities based on standards, rules, procedures, recommendations, and global agreements.

Internet governance's mission involves, equally, the stable and secure operation and continuing evolution and widening deployment of the Internet in a free, safe and open development environment.

Internet governance should be multistakeholder in scope, with the participation of governments, private sector, civil society, academic and international organizations, including democratic, multilateral, and transparent decision-making.

While scenarios, depending on the qualifications of the proponent, might involve any number of Working Group on Internet Governance’s (WGIG) long list of issues, the scenario advanced here pertains to four central needs of worldwide Internet governance:

-

management of domain names, IP numbers and protocols, today under the coordination of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN);

planning and standardization of regional and international interconnection (transit and peering);

establishment of standards or consensus recommendations for inter-country interconnection cost apportionment;

funding for self-sustainable operation and development of the global Internet governance system.

Choice of these components does not mean they are more or less important than others, nor that other components could or could not be also handled within the proposed institutional scenario. On the other hand, these seem to be key issues which are centrally brought to the fore in the discussions regarding a new institutional structure for Internet governance.

Only for the first need is there a functioning structure. This structure, with ICANN at the top, is the object of intense debate driven by strongly divergent opinions regarding the effectiveness of its representation, participation, and autonomy, as well as its dubious international nature. This proposal tries to present one of the possible scenarios of change, in which ICANN decentralizes part of its attributions and formalizes at the same time its status as a real international or global organization. In other words, the idea is to decentralize functions derived from the above needs into a group of coordinated international organizations.

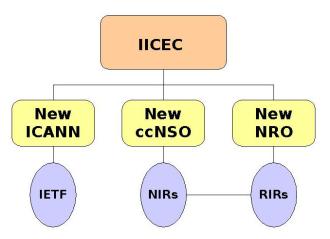

As a result, three organizations would share responsibilities for requirements [1] and [2] above, and provide support for need [3]: the new ICANN, for the root system, protocols, and generic Top Level Domains (gTLDs); the new ccNSO for the root system and country code Top Level Domains (ccTLDs); and the new NRO for Internet Protocol (IP) addresses. These three organizations would be under a global oversight and coordination Council, as described below. The entire system would be funded from a global cost apportionment schema in which every country connected to the Internet and every registry selling domains on a commercial basis would be contributors.

Other scenarios have been proposed. These range from “do not fix what is not broken,” an earlier favorite argument of ICANN and some other relevant stakeholders, which has since been revised; to the other extreme, namely drop the ICANN-based system and transfer all its attributions to a United Nations body, specifically the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Given an abundant list of intensely debated and broadly demonstrated arguments in various spaces of the Internet governance debate, none of these extremes is viable. The scenario described below refers only to the main institutions involved, and does not enter into deeper details regarding the many forms of relationship and roles of various other existing institutions related to the three above mentioned needs of governance.

Considering the new qualities attributed in the following scenario to the organizations involved, it will become obvious that there might be changes of names, a move which I do not dare to propose here.

This chapter does not deal with a major difficulty that would be encountered, namely describing the complex path from the current structure to the proposed scenario. Some crucial issues would have to be dealt with, including:

-

What would be the precise form of organization?

-

How would participation of all stakeholders be carried out?

-

What would be the decision-making processes and authoritative delegations?

-

With which golden rules / protective clauses would the governance system operate? Under which Statement of Principles?

A New ICANN

In this scenario, ICANN would become effectively an international organization, independent from the United Nations system; some observers prefer to call such a non-United Nations form a “global organization.” It would be headquartered in the United States, and would have similar immunity privileges as any international organization, and legal autonomy from US local, state and federal laws according to the standard practice for hosting this type of organization.

The new ICANN's Council would be far more democratic than it is today. Representation would equally include the private, civil society, and academic sectors, involving stakeholders of as many countries as possible. Since this representation on a one-to-one basis would be impossible to manage and very ineffective---we would be talking about a council with several hundred people---a regionalized balloting scheme for each interest group, in which every country in each region would be represented in an electoral committee on an equal basis, could provide a viable solution. Additionally, international organizations directly related to Internet and telecommunications infrastructure (like the ITU) would name representatives to the new ICANN's Council.

Executive management of the new ICANN would be chosen by indication and nomination through open voting of its Council members, in a configuration which guarantees representation of all stakeholders also in the executive structure. This could be done without compromising administrative efficiency, and the current ICANN Nominating Committees would cease to exist.

A New ccNSO

In this scenario, the ccNSO would no longer be a supporting organization under ICANN. It would become another international organization, also independent from the United Nations, headquartered outside of the USA, with the function of coordinating ccTLDs. The new ccNSO's institutional structure would follow the same logic of multilateral, multistakeholder, democratic and transparent participation as the new ICANN. Thus the new ICANN would directly handle only generic domain names, sponsored or un-sponsored.

Hopefully this new ccNSO could also help to stimulate more countries to treat their ccTLDs as their true country identities on the Internet. This would be must better than just giving their ccTLDs away as commodities to be marketed like gTLDs to any buyer anywhere. In some cases this commoditization of ccTLDs has contributed to make them very vulnerable to spam gangs, resulting in blacklisting to the point of temporarily isolating entire ccTLDs from the Internet.

Managing the Root System

Unlike today, the new ICANN and the new ccNSO would assume full joint responsibility for managing the root system, including the servers and database. Ideally it would be located in a physical place as neutral as possible without sacrificing stable and secure operation in any way. This includes full transfer of authority from the US government to the new ICANN and the new ccNSO regarding changes to the root zone file.

The new ICANN would no longer handle ccTLD coordination in any way. The new ccNSO would be fully responsible for any changes in the root system pertaining to ccTLDs. Worldwide governance should not mean freezing the system in its current technical architecture, precluding its evolution, so these arrangements might change in the future.

Earlier versions of this chapter explored the technical viability of “splitting the root” in two, with one piece under the new ICANN and the other under the new ccNSO. However, inherent vulnerabilities of the current DNS system, which is demonstrably quite unsafe, and the coming upgrading to DNSSec to overcome most of these faults--- which will increase DNS traffic and load on the DN servers---seem to indicate that the best scenario would continue to be the joint management of a single root system by the new ICANN and the new ccNSO. Additionally, management of the 13 main servers in root system would no longer be done on a voluntary basis, but would be a matter of a contract between server operators, the new ICANN and the new ccNSO, so as to reinforce operational accountability.

A New NRO

The NRO is the most recently created organization within the current governance system for naming and numbering. It was specifically conceived to coordinate worldwide distribution of IP numbers. In this scenario, the new NRO is a third international organization exclusively dedicated to coordinating distribution of IP numbers. The corresponding Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) function would be absorbed by the new NRO. The RIRs would be formalized as regional organizations of the new NRO. If the need arises for new IP number distribution organizations to be established besides the current five RIRs, these would also be under NRO's coordination. The NRO and RIRs would also follow the same logic of multilateral, multistakeholder, democratic and transparent participation as the new ICANN.

Thus far, there are only seven National Internet Registries (NIRs). These NIRs---in Brazil, Japan, Mexico, and elsewhere---would function in direct relationship with the corresponding RIRs, just as today. As the NIRs may be run by the ccTLD registry in each country, they might also be directly related to the new ccNSO. However, since most countries have chosen not to organize NIRs, or have not yet chosen to organize RIRs, other arrangements need to be in place to ensure every country's participation on equal footing through the corresponding RIRs in their regions.

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and other technical standards organizations would directly relate to the new ICANN. However, they would continue to work in the same manner as they do today, always emphasizing broad participation as much as possible and also relating closely to the other two international bodies.

Strategic Coordination and Oversight: the IICEC

The new ICANN, new ccNSO and new NRO would jointly form an International Internet Coordination and Evaluation Council (IICEC), with representation of the corresponding councils and executive management structures. The IICEC would be where governments are represented; ICANN's current Government Advisory Committee (GAC) would cease to exist. However, this representation would be construed in such way as to guarantee equal representation from all stakeholders, since governments would coexist on an equal decision-making basis with councilors appointed by the new ICANN, ccNSO, and NRO. A rotating form of regional and stakeholder representation could be devised to make sure total numbers of representatives of any sector are not too large.

Two alternatives for United Nations involvement in the IICEC could be envisioned:

-

The United Nations participates directly and is represented by the General Secretariat, and by a number of “tier-1” organizations and specialized agencies of the United Nations system, obviously including at least the ITU, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the United Nations Economic, Social, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

-

The United Nations has sixteen specialized agencies, like the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and so on, which generally have not been characterized by transparency and inclusive participation. Could the IICEC become a new specialized agency in which multistakeholder participation and adequate autonomy from the United Nations system is ensured?

Civil Society Representation

Civil society participation in Internet governance is a key concern and long-running topic of discussion. The scenario posed here envisions that civil society representation would be based on organizations---local, national, regional, thematic, sectoral, membership-based, etc—rather than on individual users. The individual user of the Internet is an unclassifiable category, involving everyone from everywhere, from a kid using a community telecenter to Vint Cerf. Being so broad, the category is easily manipulated in terms of promoting representative voting processes. Even the so-called “netizen” ---understood as the more “militant” or “proactive” Internet users---represents a universe of highly diverse opinions on any issue, therefore not making, for representation purposes, this group any different from any other Internet user eventually called to vote on anything. The ICANN election of regional board members, carried out in October, 2000, based on the building of a universal constituency of individual users, without counting on the record of any similar previous experience, was a disaster which hopefully will never be repeated.

One cannot pretend that nation-state logic would not influence the whole process just because the Internet is supposed to be, in our dreams, truly horizontal---with every user equal in her/his capacity to understand the votes being cast and to vote in a safe, free manner, from Saudi Arabia to Canada. By organizing the candidates and voters in five geographic regions, ICANN explicitly introduced geopolitical constraints into what was supposed to be a purely global Internet users' election. It is hard to imagine a viable global Internet users' voting system that would be immune to geopolitical interference and manipulation and would allow fair and representative one-user-one-vote direct elections.

As such, civil society representation in Internet governance structures is best done primarily through or by civil society organizations. As we all know, this is also imperfect, but at least it can be made less vulnerable to the above manipulations. At the very least, it opens up the possibility of an organized defense of principles and goals.

This view has already been considered by ICANN's At-Large Advisory Committee (ALAC), which is now carrying out a trial of a new structure based on membership organizations. This trial will need a thorough, critical evaluation. However, organized civil society participation ought to go further than the space ALAC or ICANN’s Non-Commercial User Constituency (NCUC) currently provide.

Budgetary Considerations

The costs of the proposed institutional structure would be covered by all participating countries, since the obvious counterpart to taking over more responsibility in governance is to be accountable for the self-sufficiency of the governance system. The amount of each country's contribution would be derived from a bandwidth usage apportioning model. One possibility is to derive the quotas from inter-country IP traffic statistics, regularly elaborated by NRO in coordination with the RIRs and, when applicable, the NIRs. Alternatively, international arrangements could be made to involve the ITU, in coordination with the NRO, to develop and maintain such statistics.

The inherent measurement difficulties here ought to be acknowledged, as many autonomous systems connect on their own to counterparts abroad in one-to-one traffic exchange contracts, since in most areas an optimized regional Internet Exchange Point (IXPs) is not prevalent or does not exist. Additionally, all for-profit registries, whether they are selling gTLDs or ccTLDs, would annually disburse a percentage of their gross income to contribute to cover the costs of this governance structure.

Towards Equitable Interconnection Charges

The new NRO, on a global basis, and the ITU in coordination with the RIRs in their regions, could take on the responsibility for monitoring and quantifying inter-country and inter-regional IP traffic, thus providing support to strategic planning of the regional structures of IXPs. Data gathered by that monitoring would feed a dynamic cost-sharing model of IP traffic among countries, to be built and maintained by consensus under the coordination of IICEC. It is understood that a lot of work still needs to be done here regarding the details of appropriate models that enable equitable cost apportioning. Propositions such as ITU's Recommendation D.50 on interconnection cost allocations just scratch the surface of this complex issue, although it is a welcome initiative in a field in which other players have begun to contribute with relevant proposals.

Preliminary Outline of the New Institutional Relationships

A simple and very incomplete graph of the proposed new structure is presented below.

A Comparison: The Brazilian Proposal

The process leading to the second phase of the World Summit on Information Society (WSIS) has set as one of its top priorities the formulation of a new global Internet governance mechanism. Among developing countries Brazil has been one of the most outspoken regarding the need for broad debate on the future of global Internet governance, and was one of the leading nations in the WSIS process that resulted in the formation of the Working Group on Internet Governance (WGIG).

The Brazilian government continues to seek a national consensus proposal regarding the future of global Internet governance. This is part of a broader multistakeholder initiative to establish consensus positions for the main themes of the WSIS. Brazil derives its global proposal from its national policy, which is based on the Internet Steering Committee in Brazil (CGIbr).

An Interministerial Group on the Information Society (“Grupo Interministerial da Sociedade da Informação”, GISI) has been established for this purpose, with representatives of several federal government ministries, private business, civil society organizations, and academic entities, under the coordination of the Ministry of Foreign Relations. GISI carries out periodic open meetings in Brasília to provide an opportunity for broad participation in the policy formation discussions. A GISI subgroup on Internet governance, working together with the Internet Governance Subcommittee of Brazil's Internet Steering Committee, has produced what is now being accepted as the Brazilian government's official position on the issue.

Brazil has been one of the first countries in the WSIS process to insist on the importance of considering a number of themes well beyond the mandate of ICANN in a future global Internet governance arrangement. The mechanism being proposed by Brazil bears strong similarities with the scenario presented above. The Brazilian vision involves the need to create an international and multi-institutional structure to encompass advice, conflict resolution and oversight on a broad set of governance themes, with “adequate” representation of all interest groups. Such a structure would be pluralist (multistakeholder), transparent, democratic and multilateral.

Based on the experience of its own internal arrangement for Internet governance, Brazil envisions four interest groups participating in a global mechanism:

The last two sectors should be represented by civil society organizations or associations. The reason to keep these two sectors separate is to make sure there will always be representatives from the academic/technical community as well as from non-profit, non-business organizations, whichever election/selection mechanism chooses representatives, even though they may be viewed as part of the non-profit civil society organizations' realm. The CSIGC has not been able so far to establish a consensus view on this representation structure. While most agree with Brazil that academic associations are part of civil society, there is disagreement regarding their specific representation in a new global framework.

Brazil also agrees with the WGIG in proposing a global Forum for Internet governance. However, the WGIG Report presents four models for a global mechanism and in all of them the establishment of a pluralist forum is contemplated, but relegated to an advisory role only. The Brazilian proposal extends the scope of the Forum to include coordination/oversight functions, thus proposing a single pluralist body for all governance functions.

In Brazil's scenario, ICANN--reorganized as a true global organism, independent from any country and retaining its logical infrastructure governance functions---as well as any other future Internet governance mechanisms, would be under the coordination/oversight of the global Forum. The CSIGC tends to favor an advisory Forum as a starting point, derived from the WGIG Report's Model 2. The Forum would progress to become a global, authoritative reference on Internet governance. In this way, the CSIGC proposal can be considered a subset of Brazil's proposal, as will be described below.

Brazil has detailed several aspects of its version of the global Forum, which its calls the Global Internet Governance Coordination Forum (GIGCF). The GIGCF would be autonomous and independent as regards any national government or intergovernmental organization. Brazil agrees that a formal link to the United Nations needs to be established in such a way that does not impair the four principles for process and participation---multilateralism, democracy, transparency and pluralism.

Some of the basic assumptions for the creation of the GIGCF, according to Brazil, are:

-

Existing institutions which are involved in Internet governance must adapt to the above four principles.

-

The GIGCF’s working agenda should be broad and include all aspects of Internet governance.

-

The GIGCF’s structure should include an intergovernmental decision-making instance dealing with Internet governance aspects which impact on national policies.

-

The GIGCF’s implementation must be carried out in such a way to ensure stability and continuous development of the Internet.

-

The governance model adopted in Brazil could serve as a reference to build the GIGCF, as well as to establish cooperation and exchange of experiences in structuring national governance models, in such a way as to facilitate participation of the national communities in the global Forum.

The last assumption refers to paragraph 73(b) of the WGIG Report, which recommends, “that coordination be established among all stakeholders at the national level and a multi-stakeholder national Internet governance steering committee or similar body be set up.” The WGIG does not go as far as recommending explicitly the governance mechanism adopted in Brazil. The Brazilian model would conflict with national policies adopted in several countries, some of which have simply contracted a commercial incumbent to sell their ccTLDs in the world market, but suggests steps be taken in a similar direction.

Details of the Brazilian Proposal

As mentioned, beyond the models presented in the WGIG Report, Brazil suggests the creation of a single body with multiple functions, and which should as a whole be multistakeholder, democratic, transparent, and multilateral---the meaning of these features basically coincides with the WGIG's vision. Although the details of the Brazilian position are still being discussed, consensus is being reached around a fourteen-point proposal regarding the GIGCF. Each of these is listed below.

1. The GIGCF should be a global space for coordination and discussion of all governance issues, as well as to support development of global policies for the Internet.

The GIGCF is seen as a policy formulator operating, depending on the issue, in advisory, authoritative, coordination, oversight, and/or arbitration roles. It gets input from already existing technical, regulatory and advisory agencies and organizations, and is regarded by these entities as authoritative on Internet-related matters pertaining to their fields of activity.

This point shows there is a lot of work to be done in establishing precise roles and specific mechanisms (including delegation of roles to organizations either existing or to be created) at different levels and instances of oversight, regulation, arbitration and so on.

2. The GIGCF should coordinate a broad spectrum of governance activities.

This point is singled out to emphasize the importance of an overall mechanism in response to the non-existence of a governance instance consolidating all Internet-related issues.

3. The GIGCF should be pluralist or multistakeholder.

The Brazilian vision here is similar to the one adopted for its national governance body. The way it envisions national governments' participation is described in the next point.

4. The GIGCF should include an intergovernmental mechanism through which governments exert their responsibilities regarding Internet-related aspects of public policy.

This is one of the most relevant topics in the Brazilian proposal, and depending on the way it is presented it raises some controversy, particularly from the camp that wants to extend the ICANN model to all aspects of global governance. Brazil wants a Forum with full participation of all sectors in the building of recommendations and definitions of policies and international agreements. However, recommendations or regulations which are seen by governments to have implications in national public policy should be considered by the GIGCF’s intergovernmental instance before any approval, following a clearly established procedure. Contrary to certain declarations or interpretations, there is no mention of the ITU or any other existing body as a replacement for ICANN in the governance of the logical infrastructure.

Of practical relevance is the fact that Brazil does not see the intergovernmental component of the GIGCF discussing and deliberating on all issues as a separate body. Rather it envisions representatives of the intergovernmental component participating in the overall processes of the Forum, which would remit to it the policy-related issues only.

5. The GIGCF, and any global governance mechanism, should not be under the jurisdiction of any specific country.

This is the expression of the WGIG Report's paragraph 48, which states:

The WGIG recognized that any organizational form for the governance function/oversight function should adhere to the following principles:

-

No single Government should have a pre-eminent role in relation to international Internet governance.

-

The organizational form for the governance function will be multilateral, transparent and democratic, with the full involvement of Governments, private sector, civil society and international organizations.

-

The organizational form for the governance function will involve all stakeholders and relevant intergovernmental and international organizations within their respective roles.

In addition, Brazil sees the GIGCF as an international organism formally recognized by the United Nations, and legitimized by a specific international treaty. The CSIGC also agrees to a formal relationship with the United Nations, preferably directly with the Secretariat-General, the terms of which need to be defined.

6. The GIGCF should work for the global public interest.

This raises in particular arbitration issues (how to prevent or circumvent impasses resulting from national conflicts of interest which might block processes) and balanced participation issues (how to ensure developed and developing countries, private and public interests, commercial and non-commercial interests are equally represented).

7. The GIGCF should abide by the criteria of transparency, democracy and multilateralism.

These are aspects already expressed in the WSIS Geneva resolutions.

8. Each one of the representatives of the four interest groups---governments, business associations, non-profit non-business organizations, and academic/technical associations---ought to establish clear accountability rules regarding their constituencies.

Brazil emphasizes two particular issues in this regard: how to select and ensure global accountability of the non-governmental representatives and how to ensure qualified participation of the non-governmental sectors from developing countries. This is an explicit concern of the CSIGC as well.

9. Regarding existing global organizations dealing with specific, Internet-related issues, the Forum function should include coordinating these organizations instead of replacing them.

This is a significant proposition: the approach is to build on existing expertise and organizations, not on starting from scratch, and to consolidate global governance in a coordinated fashion around existing organizations for the functions these are able to carry out, as well as help build new mechanisms when needed for components not yet properly covered. This means relying not only on the capabilities of ICANN, but also on several of the existing United Nations agencies and other technical bodies.

10. The GIGCF should operate with efficacy and practicality to ensure rapid decision-making processes, in keeping with the dynamics of Internet expansion and evolution.

Brazil suggests mechanisms of representation in which the Forum is constituted by a relatively small number of representatives legitimately expressing the interests of all sectors. This requires adequate global procedures and mechanisms to ensure transparent and democracy election and selection processes on a country and regional basis.

11. The GIGCF should be flexible and adaptable to adjust its agenda and processes to the rapid evolution of the Internet.

This emphasizes new issues evolving from deployment of advanced technologies, the consequences of rapid convergence of different media and communications systems to the Internet, and so on. These developments in their turn might require a corresponding evolution in certain forum functions, rules, standards and recommendations.

12. The GIGCF should be able to act as an efficient clearing house collecting needs from the several interest groups and dispatching them (or the resulting resolutions) to the relevant organizations.

Brazil stresses that in this respect the Forum should rely heavily on the latest Internet-based knowledge management technologies, expediting transparency, democratic procedures and the clearing house functions, as well as relying on open online and face-to-face meetings as much as possible.

13. The GIGCF should be authoritative in its capacity to resolve conflicts and coordinate the work of different organizations.

Brazil sees this authoritative capacity defined by one or more international treaties or conventions, as well as specific contracts and memos of understanding.

14. The GIGCF should be self-sustained.

The Forum should be supported by an efficient, lightweight technical/administrative infrastructure. Meetings should as much as possible be online using the best Internet multimedia resources. Many activities would be carried out through specialized working groups, usually constituted of volunteers compensated for travel and perdiem expenses when needed. These methods should help reduce the operational budget.

Funding for the GIGCF should come from all participating sectors according to their capacities. Ceilings for specific contributions should be established in order to avoid both barriers to entry and hegemonic positions. ICANN is the anti-example for this proposal, as its income comes basically from the major gTLD registries.

|